Actor Paul Darrow’s death was announced yesterday. In August 1980, I interviewed him for Marvel Comics’ Starburst magazine. He was then starring as Avon in Terry Nation’s BBC TV science fantasy series Blake’s 7.

When, in a 1978 interview, I had asked Terry Nation about the character of Avon, he told me Paul Darrow “took hold of the part and made it his own. It could have been a very dull role, but this particular actor took hold of it and gave it much better dimensions than I’d ever put on paper. He is an enormously popular character. He is incredibly popular – and rightly so. He’s a good actor. I think he’s terrific.”

In a December 1980 interview, co-star Jacqueline Pearce, who played Servalan in Blake’s 7, told me: “Paul always knows what he’s doing in front of a camera; technically, he’s quite brilliant”.

In this first extract from my 1980 interview with Paul Darrow, he talks about how an actor can play “a bastard” sympathetically and, by talking about Avon, perhaps also reveals a lot of his own thoughts.

You do not have to have seen Blake’s 7…

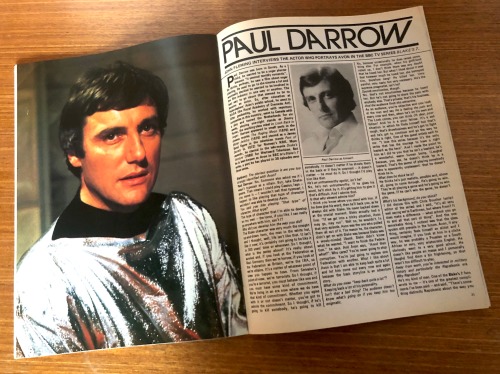

This is the 1980 article, starting with its introduction…

Paul Darrow was born in Surrey. As a child, he wanted to be a sugar planter because “it seemed terribly romantic”. He thinks, perhaps, he saw a film about sugar planting. He used to go to the cinema a lot and eventually decided he wanted to be involved in the film industry in one way or another. The best way to go about that seemed to be to become an actor. So, after education at Haberdashers’ Aske’s public school, he went to RADA (the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art) in London.

After graduating, he worked with repertory companies in this country, went to Canada with a play and toured the Netherlands for six weeks, playing one-night stands as Jimmy Porter, the working class rebel in Look Back in Anger.

Darrow appeared in small parts in cinema movies The Raging Moon (1970) and Mister Jericho (1970) and starred as a James Bond figure in the television movie Port of Secrets (1974) for Norway’s NRK. More recently, he starred in the tele-movie Drake’s Venture (1980) for Westward Television. But he is best-known as Avon in BBC TV’s Blake’s 7 series, a part he has played in 38 episodes over three series.

Paul Darrow’s autobiography, published in 2006

JOHN: The obvious question is are you too strongly identified with Avon?

PAUL: No. Someone else asked me if I wasn’t typecast as a villain. But, take Shakespeare. That means I could play Cassius, Iago – you name it – I wouldn’t call that typecast. I happen to like playing that type of character and also I was able to develop Avon.

JOHN: You said you like playing “that type” of character. What type?

PAUL: The type of character that I’m able to develop on my own – the loner, if you like. I can really go anywhere with him, can’t I?

JOHN: Why did you develop him the way you did?

PAUL: The Blake character was very much the straight up-and-down hero, the man in the white hat, and I thought: Well, life isn’t like that. It isn’t like it now; it’s certainly not going to be like that in 300 years’ time or whenever. So I thought: What is the series about? It’s really about survival and, if you look at the Federation as Nazi Germany, then we’re heroes; if you look on the Federation as Britain, we’re the IRA, so we’re villains. It’s a matter of whatever point of view you happen to have.

From Servalan’s point of view, we’re terrorists.

So I thought: If you’re a terrorist, you must behave like one and you must have some kind of commitment. Whether you agree with it or not doesn’t matter; you’ve got to admire the commitment. So I thought: If he’s going to kill somebody, he’s going to kill somebody. It doesn’t matter if he shoots them in the back or if they’re unarmed – it doesn’t matter – he MUST do it. So I thought I’d play him like that.

JOHN: He’s an untrustworthy egotist, isn’t he?

PAUL: No, he’s not untrustworthy. If he gives his word, he’ll stick by it. It’s getting him to give it that’s difficult. And I admire that.

JOHN: Is that why viewers admire him?

PAUL: I think you know where you stand with him. If he does give his word, then he’ll back you, as he always did with Blake. He never backed down at the crucial moment. Blake actually had a line: “If we get into a tricky situation, Avon may go, may run”. Well, no, he wouldn’t. In that very episode, Avon was the one who pulled them all out of it. The reason he, the character, didn’t get on with Blake was because Blake was a woolly-minded liberal.

Blake didn’t know what he wanted.

“I want to finish the Federation,” he says.

And Avon says: “And then what?”

Who cares? You’re never going to stop corruption. You’re just going to replace one Federation with another. What I like about Avon is that I am able to keep back quite a lot and let him come out every now and then because the basic storyline is an adventure story.

JOHN: What do you mean “keep back quite a lot”?

PAUL: Keeping back a lot of his personality.

JOHN: Isn’t that a bad thing? The audience doesn’t know what’s going on if you keep him too enigmatic.

PAUL: No, because occasionally he does reveal something else. For example, when his girlfriend rolled up, I don’t think there was any doubt that he loved her. But what I liked about it was that, however much he loved her, she betrayed him, therefore – BANG! He killed her. Very painful, very nasty but very necessary. He’s the supreme pragmatist, isn’t he?

JOHN: Sounds emotionless, though.

PAUL: No, that’s not emotionless, because he loved her. But he’s not going to share the pain with anybody else. That’s private; that’s his business.

JOHN: And the audience finds this attractive…

PAUL: As an audience, you’re objective and you look at the man and say He is feeling the pain and, every now and then, when he’s on his own and The Look comes, you can think Oh dear! Poor fellow! And he is a poor fellow. It’s a sad situation in which he finds himself but that’s tough, that’s show business and he’s got to fight and he’s got to continue and go the way he thinks is right.

One of the guest artists said to me: “I love this series because it’s the only series that has the courage to have a right bastard as the hero”.

And I made the point to him as I did to you that he isn’t a bastard; he’s a wonderful, warm human being. (LAUGHS) Because, you see he doesn’t think he is a bastard. That’s the secret of playing somebody who is apparently unpleasant: that he doesn’t think he is.

JOHN: What does he think he is?

PAUL: He thinks he’s just realistic, sensible and, above all, going to come through. He’s going to win. They’re all playing a game and he’s going to win the game. If he can’t win the game, he doesn’t play.

JOHN: What’s his background, do you think?

“What’s his background, do you think?”

PAUL: I did discuss this with Chris Boucher (script editor of the series) and I said: “It’s all very well saying we’re Earthmen, but where from? It does make a difference what school you go to and all that sort of thing.”

And the one remarkable thing I noticed was that the class system still prevails in the future. Avon, if anything, certainly feels himself an elitist and I would imagine, if you look at him in a cliché way, he was probably a Prussian or a South African or very, very aristocratic English.

He obviously went to a very good school. He doesn’t like people en masse and I personally (LAUGHS) find them a bit frightening, so that wasn’t too difficult to play.

JOHN: Away from work, you’re interested in military history and particularly the Napoleonic era. Why Napoleon?

PAUL: He’s my kind of man. One of the Blake’s 7 fans wore to me – it’s one of the greatest compliments I’ve been paid – and said: “There’s something distinctly Napoleonic about the way you play Avon”. That was a compliment.

JOHN: Why is he your kind of man?

PAUL: Because he was a realist. He was able to combine romantic idealism with realism. Somebody once said to him: “We can attack in flank on the Austrian Army, but it will mean going through these rather beautiful gardens and destroying them.”

Napoleon said: “How long will it take you to do it?”

And he said something like: “Forty minutes, preserving the gardens.”

And Napoleon says: “How long will it take not preserving the gardens?”

And he says: “Twenty minutes”. Half the time.

So Napoleon says: “Go through the gardens. Win. We can always rebuild the gardens.”

Which is sensible.

JOHN: Very Avonesque.

PAUL: Yes. He wouldn’t think twice. The actor Audie Murphy, in his book To Hell and Back, wrote about when he was in the American Army in Sicily and they suddenly came across two Italian officers riding two magnificent white horses.

They were armed; they came round the corner and the American officer and all his men froze. Murphy went down on one knee and gunned down the Italians and the horses. He had no choice and that was the professional in him. When everybody else froze, those Italians could have blown them to smithereens.

Jacqueline Pearce as Servalan with Paul Darrow as Avon…

So the kind of realism that allows a man to do something like that instinctively – sad though it is to kill beautiful horses – appeals to me. He was the most decorated hero of World War II; he was fascinating.

You see, being brought up in the cinema, those are the sort of people I admire. I was brought up on Humphrey Bogart and a situation where men were men and women were women. Now, alright, that’s a cliché, but I like that. I don’t like all this unisex stuff.

… CONTINUED HERE …

Thanks for putting this up, John. I remember reading the original interview in Starburst during my youth. Actually, it revives fond memories of a long-ago, more innocent and more virtuous time… When your number-one role model would gun down his best friend in cold blood and try to save his skin by chucking his second-best friend out of an air-lock.