If you have popped in to read this blog for a bit of levity, I suggest you give it a miss today and try tomorrow, when mild titter-making may make a welcome reappearance.

At the weekend, I got an unexpected Facebook message from someone I do not know.

At first, I thought it might lead on to some scam in which I would be told I could get access to millions in a Nigerian bank account if I gave out my own bank details. But, no, it was a genuine question. It was (and this is true):

“I know these times is not very easy but I would like to ask you about purpose of life what do you think most important thing in this life (sorry for my language I am just began learn English)”

After a couple of Facebook messages, my reply (again, this is true) was:

“Purpose? None. Just try not to hurt other people. The most important thing, sadly – and it took me a lifetime to realise this – is money. Because without it everything else is difficult. Money will not bring you happiness but, if you are unhappy, it will make being unhappy less uncomfortable! Friendship and relationships, of course, are what matter in the long-term, but never underestimate money… and trying not to hurt other people…”

In the last couple of days, a couple of people have asked me if I saw last week’s screening by BBC TV of the movie The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas (set in a World War Two concentration camp). And, yesterday, someone asked if I saw Sunday’s ITV1 drama Appropriate Adult about the multiple murderer Fred West.

My answer was that I did not watch either of them because I really did not think seeing them would make me a better person. Do I really want to sit through something harrowing and/or feel uplifted at the end from watching the fictionalised reality of something obscene?

For perhaps 25 years, I had a paperback version of Emlyn Williams’ highly-regarded 1968 book Beyond Belief, about the Moors Murders. I could never bring myself to read it and, three years ago, a year after after my mother died, I took it to a charity bookshop because I knew I would never read it. It would not increase my sympathy or empathy for other people’s suffering.

When I was about 11 or 12, I saw film footage shot when the first Allied troops went into Belsen in 1945. It was one of the first concentration camps to be liberated and the cameras went in with the first troops; later, the cameras went into camps after they had been partially ‘cleaned up’.

The footage was and is the worst thing I have ever seen. I remember seeing a pile of skeletons. Dead skeletons all piled up. Except, then, one moved – he or she was still alive and, I think, got up and walked – staggered – slowly like some unreal Ray Harryhausen stop-frame animated figure.

Wikipedia currently quotes BBC reporter Richard Dimbleby, who was there when the camp was ‘liberated’:

“Here over an acre of ground lay dead and dying people. You could not see which was which… The living lay with their heads against the corpses and around them moved the awful, ghostly procession of emaciated, aimless people, with nothing to do and with no hope of life, unable to move out of your way, unable to look at the terrible sights around them… Babies had been born here, tiny wizened things that could not live… A mother, driven mad, screamed at a British sentry to give her milk for her child, and thrust the tiny mite into his arms, then ran off, crying terribly. He opened the bundle and found the baby had been dead for days. This day at Belsen was the most horrible of my life.”

I only saw the film footage. What on earth it must have been like to be there on that day I cannot imagine.

It made me realise when I was 11 or 12 what people are capable of doing and it made me put anything that has happened since into some perspective. I think it would do most people the world of good to see the footage of Belsen when they are 11 or 12, at an impressionable age before they are capable of putting up psychological barriers to defend themselves from what they see.

The other horror I am, in a sense, glad I saw were the killing fields of Choeung Ek in Cambodia in 1989. They were the killing fields for the capital Phnom Penh. Before the Khmer Rouge took power, the fields (formerly an orchard and Chinese graveyard) had apparently been somewhere families went for tranquil days when they were not working.

It was not the killing fields which upset me so much.

In the killing fields were tiny, tiny shards of shattered, broken-off bones on the ground, there were occasional tiny little pieces of torn clothing and there were the covered-over pits where no grass grew. But they were just objects – bits of bone, fabric, earth.

It was Tuol Sleng – S-21 which upset me – the ‘interrogation’ centre which had previously been a high school in Phnom Penh.

At Tuol Sleng, the former classrooms had been divided by roughly-built brick walls into thin prison cells… and then there were the confessions. The Khmer Rouge had had an almost Germanic efficiency, perhaps because they had been so sure they were in the right. After torture, people had admitted their guilt and their confessions had all been carefully written before they were taken off in trucks to be killed in the fields of Choeung Ek, usually by agricultural implements because why waste bullets?

After torture, they confessed they had worked for the previous regime – behind the counter in a post office or in the Ministry of Agriculture or whatever their crime had been; they had been a schoolteacher or they had worn spectacles or were family relations of people who were guilty of any of the many capital offences decided-on by the Khmer Rouge.

But it was not the confessions which upset me so much. They were just bits of paper, even if they had real people’s words on them. It was the photographs.

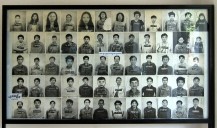

The Khmer Rouge had indeed been very efficient. They had photographed each and every guilty person before they were driven off to be killed in the fields. Small portrait-style chest and head shots of everyone. And hundreds of these photographs papered every inch of the walls of the two entrance rooms to Tuol Sleng.

Hundreds of photographs. Hundreds of faces. Hundreds of eyes staring at you.

It was like the American radio reporter’s commentary as he watched the Hindenburg airship burst into flames: “Oh the humanity!… Oh the humanity!”

And all the hundreds of people in the photographs at Tuol Sleng had exactly the same look in their eyes as they stared into the Khmer Rouge photographer’s camera. Each one of them knew they were going to die and you could see the look of hopeless resignation in their eyes; they knew they would be dead very soon.

It was like Richard Dimbleby’s description of Belsen: a “ghostly procession of emaciated, aimless people, with nothing to do and with no hope of life, unable to move out of your way, unable to look at the terrible sights around them…” because they knew for certain that they would be dead soon. The look in their eyes was hopelessness.

I remember when I was back in London, crossing Shaftesbury Avenue near its junction with Piccadilly Circus and I cried for no reason, remembering the look in those people’s eyes.

I think, when I saw the film of Belsen when I was 11 or 12 and when I saw the hundreds of photographs of people at Tuol Sleng, I was a better person for having seen what I saw. Perhaps a bit more sympathetic. But I do not think watching the Fred West drama or The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas or reading Beyond Reason would have increased my empathy.

They were all, to an extent recreating evil but they were not the evil itself.

I saw Schindler’s List when it came out because it was a Spielberg film and I was interested to see how he had filmed it. But you cannot make a film about concentration camps.

I remember when the acclaimed US TV mIni-series Holocaust was screened. I had no interest in seeing it because, however good the acting and direction and however much the Method actors starved themselves for their roles, they could not replicate the walking dead of Belsen and all the other work camps – Belsen was a work camp, not a death production line like Auschwitz.

If what people see and remember are highly-acclaimed TV series and movies like Holocaust and The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas and Schindler’s List, then what they see is, in a way, what they and their brain will remember as the reality.

But the reality was not the TV series and the movies; the reality was the film shot in Belsen and the photographs taken by the Khmer Rouge of the faces and the eyes of their victims.

Seeing them, I have always been aware that people are capable of anything.

When I was newly-18 I tried to kill myself. Unforgivable, because of the pain I inflicted on my parents. Blinded by pain and incomprehension, they visited me in hospital. Trying to be kind and considerate and loving, they brought me some oranges to eat and, to cut them, a short knife with a sharp, stainless-steel, serrated blade. After they had left, under the bedclothes, I ran my finger along the knife a few times and ran the knife across my wrist a few times. Eventually, I gave it to a nurse.

What I learnt was never to trust anyone because even someone with your best interests at heart can destroy you without meaning to.

And they are the good guys.

The world is full of genuine bad guys who actively want to harm you and destroy you because it makes them feel good.

I am sure the guards at Belsen got a hard-on watching people die.

All you can do is carry on, eat chocolate, laugh at the pointlessness of it all and die. When you are lying on a bed, staring at the ceiling, unable to blink or close your eyes and all you can hear is your own death rattle, nothing matters – not career, not money, not anything except the memory of friendships and relationships.

I guess.

Who knows?

I watched my father die like that.

No punchline.

Mild titters may re-appear tomorrow.

PLEASE SHARE THIS BLOG VIA: