Once, when I was working for the Discovery Channel, I had to make a TV trailer for a rather suspect documentary on the Waffen-SS.

I say ‘suspect’ because it started off with the words:

“The Waffen-SS is renowned throughout the world for its efficiency…”

Yes. I thought. Yes, but… and it is a very big But.

These last few months, I have been reminded of that by the Syrian Army’s wide-ranging put-down of the Syrian uprising. Very efficient. But…

I only had one encounter with the Syrian Army.

I visited Lebanon at the very end of 1993, almost four years after the Lebanese Civil War had sort-of ended. It seemed like a good idea at the time.

I had tried to combine my trip to Lebanon with a visit to Syria to see the ruins of Palmyra but the Syrians had refused me an entry visa without explanation. My passport said my occupation was “writer” which probably did not help, though this had proved no problem in Albania under Enver Hoxha nor in North Korea under the Great Leader Kim Il-sung.

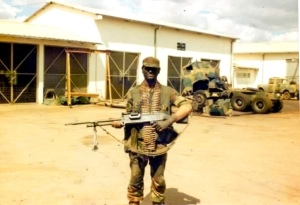

In Beirut at that time, there were still Syrian ‘peacekeeping’ troops manning occasional sandbagged emplacements at crossroads and roundabouts.

Beirut was a strange city. At rush hour time, there were traffic jams of Mercedes-Benzes – almost all the taxis were Mercedes Benz. Money was flooding back into what had been the banking centre of the Middle East. You could walk along a street and it would seem perfectly normal and peaceful. But you could turn a corner and there would immediately be two or three blocks of burnt-out, bombarded skeleton buildings, utterly devastated, like visions of Berlin in 1946. You could not go up those streets nor into the buildings because there were mines and unexploded shells.

This is an extract from my diary.

FRIDAY 7th JANUARY 1994 – BEIRUT

I have a sneaking feeling we are the only guests in this hotel. We never see anyone else at breakfast. Never share lifts with anyone. The room next to us, where we heard a loud argument late one night, has no beds. I just looked in. Just two sofas.

The Syrian soldiers have no problem with accommodation. No tents on the wet ground for them. They just live in some of the skeleton buildings. We saw them camp-bedded in the Hotel St-Georges yesterday and, round the corner from our hotel, they are living in three storeys of a burnt-out building – usually we see some playing cards at a table on the first floor. No walls, of course. Like several around here, it is a building reduced to a vertical grid of open-fronted concrete boxes.

Nearby, there is a sandbagged emplacement in the middle of a junction at the far side of which is a Kentucky Fried Chicken/Baskin Robbins emporium in all its plastic red, white and pink glory. Two soldiers with machine guns stand inside the ring of sandbags, which has a little metal roof over it. There are usually at least three other soldiers standing around, looking in different directions, either in the roadway or on the surrounding pavements or both. Yesterday, there were five soldiers and a lorry. They do not seem trigger-happy; but they seem alert.

Today, a man on the seafront pavement saw the Pentax camera hanging over my shoulder, half-hidden under my arm, and decided to shake my hand.

“Welcome to Lebanon!” he said.

I thought he did this to practice his English but, eventually, he invited me over to buy a tea from his van. It was impressive to see Lebanese entrepreneurial skills re-emerging.

As he made the offer, a military jet flew low overhead and a couple of klaxoned motorbikes ee-aw-ee-aw-ee-aw-ed out of a junction, leading a four-car convoy and, a little later, a couple more jet fighters flew over and round in a complete circle.

On Tuesday, I was woken up by the sound of two jets flying fast and low one after the other.

I walked down as far as the Summerland Hotel – which I knew for its peach melba, chattering American financier, vast swimming pool and supermarket. A man with a Buick told me his sister had bought a nearby flat for $750,000.

I looked at my map for directions and left the Summerland Hotel for the city centre but a gent in front of me pointed out that two soldiers behind me wanted me to stop. These two soldiers – then a third – then a fourth – then a fifth – wanted to see what I was reading. None of the five could speak any English or French at all. But they wanted to know if I had been taking any photographs. (My Pentax was over my shoulder; the smaller Minox camera was invisible in my pocket.)

They wanted to know where I got the map. I had bought it from a shop in one of Beirut’s main streets. Fortunately I still had it in the paper bag and could point at it. They did not seem to have seen any map nor knew one existed. They were not content. I showed them my passport, which the soldier in charge (in his twenties) did not really understand. He was more interested in my Middle East Airlines ticket stub. He must have read the Arabic on the back of the stub about four times at various points. It says (in multiple languages):

“Kindly reconfirm your reservation between 10 and 3 days before date of departure to guarantee your seat. Otherwise your reservation will be cancelled.”

This fascinated him so much we all went over to a guard post, then into an open area between two nearby buildings. I explained my week of merry jaunts around Lebanon by pointing to the days in my diary. But he was more interested in three Daily Telegraph Holiday Offer coupons I had torn out for a friend. They showed drawings of an aircraft, a cruise ship, a sun, a family and a bar code. He looked through these slowly twice.

As he was doing this, I palmed something else that was in my diary – a letter from a friend in Norfolk who sends letters/parcels to a ten year old girl in Beirut. It read:

“If you really want to live dangerously in Beirut, the address to seek out is (and it gave the girl’s name and address). Her dad was a policeman in the Lebanese Internal Security Forces so TAKE CARE!”

I thought it wise to palm this even though, clearly, none of the soldiers understood English.

By this time, a Syrian Army Intelligence officer in civilian clothes had been brought over to our group. He was older, maybe mid-40s, and very relaxed. He also understood and spoke basic English.

We went through the map, photos etc again. He seemed to have been told the soldiers saw me taking photos which, ironically, I had not been. He, too, seemed surprised I had a map. He asked more detailed questions – or, rather, I volunteered information – travel agency in Beirut, hotel, route, the diary again.

All those many TV years of obsequious amiability, smiling, wittering and keeping calm came to fruition. If you can tell children and parents their appearance on national TV has been cancelled, then gents with battledress toting Kalashnikovs are less of a worry.

But only slightly.

The Intelligence man asked me:

“What is your job?”

“I write for children,” I told him, on the basis this had done me no harm in (an even dodgier country which shall be nameless until next year) and my visa said ‘Writer’ but I did slightly worry that the Syrians had refused me a visa.

“Mmmm…” the Intelligence man said.

The main military man went off with my passport and the Beirut travel agent’s card. I was left alone with Intelligence man in civilian clothes and a very young soldier fiddling absentmindedly with the trigger of his Kalashnikov. He could shoot his own ear off I thought.

“Are you in Lebanon with others?” the Intelligence man asked.

“One other person.” I replied. “I think he is still asleep back at the hotel.”

I was in obsequious/amiable chatting mode.

The Intelligence man had come back to Lebanon from the US one year ago. He was not surprised a flat in this neighbourhood went for $750,000. I asked how much flats in the building to our right would cost. He said about $400,000 with three bedrooms.

He was polite, amiable and smiling. But sometimes, when I was not looking at him directly, his smile would drop a little.

“Your British Foreign Secretary Mr Hurd went from Beirut to Israel this week. What do you think of the Israeli-Arab problems?” he asked me, then realised it was too blatant a question and back-tracked.

The main soldier came back.

They took me into a tent in the ground floor of the house to our left and we went through the map again.

I showed them my route.

“What photographs have you taken today?”

I could not remember anything except the devastated Holiday Inn area by the sea (not a good thing to mention) so I said Martyr’s Square and pointed it out on the map.

None of them (about five) had heard of Place des Martyrs/Martyr’s Square, the main – indeed only big – square in the city; and they had difficulty looking at the map and figuring out where it was in town.

You would think soldiers could read a map and would know the local layout, I thought.

It was around this time they started mentioning you need a licence to shoot film.

“You need a licence to shoot film,” I was told. “Do you have one?”

“No.”

In fact, this cannot be true and, indeed, I have always carried the Pentax in full view (though mostly using the Minox).

Yesterday, a soldier saw the Pentax over my shoulder

“You cannot take film here,” he said. “Bombs… Boom!” He pointed at the ground. “Not here. Poof!…Bombs!… Boom!”

But he never said I needed a licence to film. I presume today they were trying to intimidate me.

I had been offering to take the film out of the camera and give it to them and they now decided I had to… take the film out of the camera and give it to them.

I could not remember what was on the film – possibly photos of the bombed American Embassy, the Holiday Inn, the Hotel St-Georges and the bay by these hotels.

I dabbled with the idea of opening the back of the camera, then unspooling the film for them, but figured it would be too obvious I was destroying the pictures I had taken. So I just rewound it and gave them the film as it was. Assuming they would not develop it by 0730 tomorrow anyway (my take-off time).

Everything was very relaxed after that. I was at my most obsequiously polite.

The Intelligence officer and the main soldier took me outside. I thanked the soldier three times for his politeness. The Intelligence officer said, “I hope you understood it is a difficult time… only for security reasons… A difficult time… very sensitive… for the country’s security and your own… A difficult time.”

I assume it was just a Jobsworth affair with the soldiers trying to get brownie points from their superiors for being alert to security dangers.

They had not searched me. If they had, they would have found the Minox camera and four new rolls of film in my trouser pockets.

When I left, I walked back to my hotel and switched on the BBC World Service, which was transmitting a report on the Jewish community in Cuba, with various Jewish songs being sung. I decided to switch it off.

Later, I went out and bought Tuesday’s Arab Times, which bills itself as “The First English Language Daily in Free Kuwait”. It reports that, on Monday, the day we were in Tyre and Sidon in South Lebanon, “Guerrilla factions in South Lebanon went on maximum alert in a pre-emptive move designed to avert Israeli strikes expected to accompany the forthcoming Syrian-American summit scheduled for mid-January.”

The Arab Times went on to report that, on Monday, the Israelis (via their ‘South Lebanon Army’ militia) “carried out a reconnaissance by fire tactic at 9.00am by firing six 120mm mortar rounds at a hill overlooking the southern Lebanese market town of Nabatiyey.”

What an interesting use of the word “reconnaisance” I thought.

They are all mad.

All sides.

Everything is out of control.

PLEASE SHARE THIS BLOG VIA: